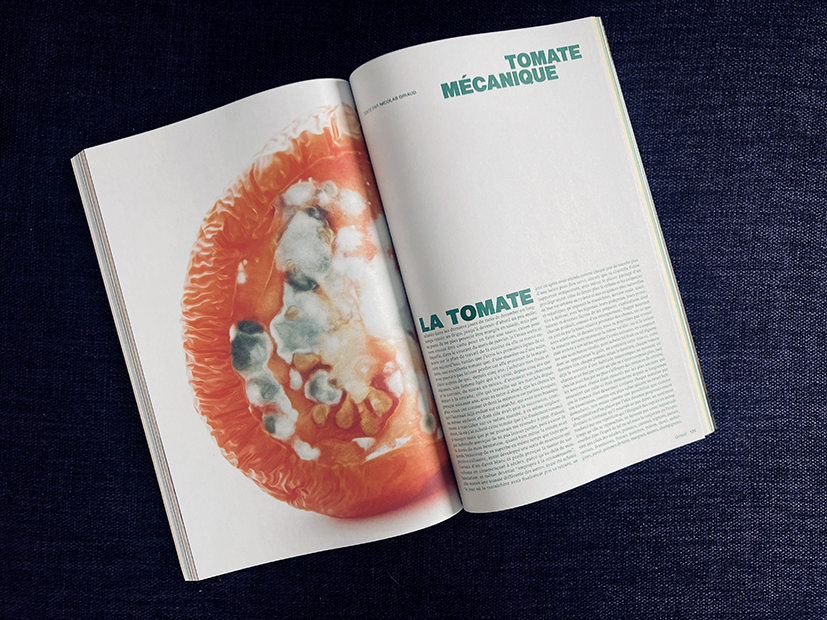

A clockwork tomato, 2018

The tomato, bought in the last days of December, had been in the fridge for quite some time, first growing a little softer, to the point where it could no longer be eaten in a salad, but could still be cooked to make a sauce, being the reason why, at some point earlier in the month of January, I had taken it out and placed it on the kitchen counter where it remains sitting to this day, as I write the first lines of this text, an excellent tomato which, in some form or fashion, I had to use, as it had come from the market gardener from whom I have been buying my fruit and vegetables for the last five years, an older woman who constantly and frequently, for the five years that I have grown to know her, announced her imminent retirement, she who had been working on the markets for nearly sixty years, first with her mother, whom the oldest clients knew and whose memory is sometimes evoked, who brought the child to the market, the child, now a woman herself, who sold her wares at the same place, following in her mother’s footsteps, continuing to work in the same market, at the same place, the same place where I bought this tomato that I finally gave up on eating but could not bring myself to throw away, firstly due to an atavistic habit of not letting things go to waste, and then because of the time spent hesitating, even if the tomato had lost a lot of its allure along with any culinary prospects, having developed some kind of mold which covered it in a white duvet, and having lost almost half of its volume, as it began to dry out, as, beyond the question of my hesitation and the fact that it had become “unsuitable for consumption”, it continued to be a tomato which was different to others, having been purchased on the same day that the market gardener had retired, a day when, after having waited, like every visit to the market, for over an hour to be served, a wait that her loyal customers tolerated stoically, perhaps even sharing the pleasure of a secret privilege, that of having to bend the pace and demands of their urban lives to the more natural and organic rhythm and requirements imposed by the market gardener, serving alone, being sure to deliver, along with the vegetables, their pedigrees, their origins and various ways of preparing them, with each person benefitting from this, like a form of education, and yet nonetheless struck that day by the relative nature of the permanence of things, because whatever we bought, that last day, those varieties, would no longer be there if we came back a week later, or a year later if the season had come to an end, counting on an equally successful harvest, to buy this fruit or that vegetable whose taste we enjoy, on the contrary, this time, this final time, each apple would be the last one, each tomato was already the memory of a habit interrupted at the very moment when no-one imagined that it would ever be interrupted again, as we no longer lived in the shadow of the threat of her retirement, new clients were comforted by older ones who reassured them that it had been imminent for such a long time that the threat was now raised each week in words, like some form of added value to the weekly ritual, not so much as a possibility but more as the enhancement of a pleasure of the idea which had become so increasingly abstract and distant that it couldn’t last, a feeling which was reinforced by repetition which simultaneously placed it far from one’s mind while at the same time bringing it closer, not leaving an unspoken worry in this or that person’s mind but rather conjuring it up and then exposing it alongside the salads, leeks, carrots, onions, parsnips, cherries, raspberries, strawberries, apples, pears, beets, aubergines, parsley, potatoes, mangos, pineapples, mushrooms, tomatoes, zucchinis and zucchini flowers, and then only when it was finally over, when the vegetables had been carried home from the stall for the last time, wiped down in different kitchens, would they show themselves to be carrying this suddenly visible certainty that they were perishable, that they represented the last samples of a bygone age, this was the expired paradoxical function of this tomato which was slowly rotting on my kitchen countertop, that of maintaining a temporality, that very particular and archaic temporality of the market, and for it to keep this function it would have been necessary to warn the friend who was staying at my place for a couple of days to not throw the tomato that was sitting on the kitchen countertop away, the disproportionate attention paid to this tomato in the process of rotting was due to the image of it carrying a hypothesis within it, like a possible version of a world where it would be the principle, echoing the rotting apple exhibited by one artist, indicating that the bacteria that was developing on and in it while it rotted would be capable of destroying everything contained in a museum, the rotting power of the apple, like its twin the tomato, entered into conflict with the assumptions of the world in which I evolved on a daily basis, it transformed a bottle of orange juice into a war-zone between the entropy of liquid and the plastic immortality of the bottle, a conflict between the living and the dead, or rather perhaps between what is living and that decomposes and that which is to a certain extent living-dead, this conflict which takes place precisely between the living and the dead, between the mechanic and the organic, this conflict triggered my consideration of the tomato, because after having bought it I first went to Berlin, then to Arles, as the process of ripening was getting underway in the refrigerator in my apartment, time itself, even fragmented in different places and different time zones, continued to move forward similarly for the tomato, even as I begin this text in Los Angeles, unable to see the tomato, but knowing nonetheless that it is still sitting on the counter, on the 5th floor of the building in Paris where I was going to be living for a few more weeks, only ten or so meters from from the square that hosted the market, every Tuesday, Friday and Sunday, functioning like a biological clock, indifferent to the jet lag that I was struggling with in a Californian café, after a fourteen hour flight and the discreet ritual of these flights where one drinks a tomato juice on the plane, fittingly, something that we can imagine being an archaic form of resistance to the temporal brutality of aerial technology, blending airplane and tomato in a sort of paradoxical equation, which always reminds me of the recipe for a cocktail that was created in a ski resort almost twenty years ago and just as quickly forgotten, with only the name blood cloud remaining along with the image of a red cloud suspended within a glass, floating in pure vodka no doubt, an image that could help one to find the recipe for the cocktail, or at least to recreate it, not so much to return to a point in time out of reach but to give it form, less to produce a memory than to begin this mechanic of the mind that can deploy a world starting from an image, tying scattered spaces and moments together, similar to this text where the writing was spread over months and months, from one apartment to another, while I was taking other planes, other trains, taking up the writing elsewhere, retracing my footsteps, inhabiting new places, similar to the tomato, taken from its biotope, pulled out of the culinary circuit and now almost forgotten on a shelf, now functioning like a singular aleph or clock, measuring as it shrinks further and further, ever larger gaps in space and time.